Restoring our relationship with hímu (willow) requires human interaction rather than protection

SEPT 19, 2022

RENO, NEV.

By Robin Smuda, Climate Reporter Intern

Native Climate

Hímu

Willow

In between the high lush landscape of dáɁaw (Lake Tahoe) and the expanse of arid landscapes within the Great Basin, the Wá∙šiw have lived here and have lived with this community for countless generations. The continuation of life for the Wá∙šiw is based around plants that always stand: dá∙bal, ťá∙gɨm, and hímu. With them, survival is always possible, and they can help us understand our problems. But current viewpoints that prioritize protection over interaction with the environment are at odds with strong traditional relationships between the Wá∙šiw people and these plants.

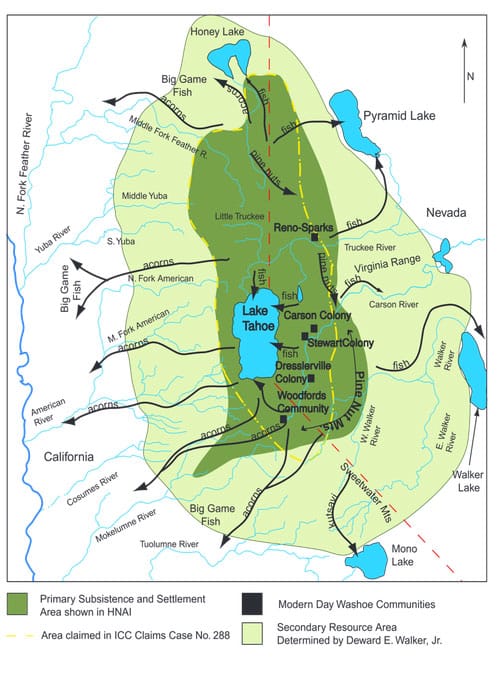

Wá∙šiw traditional homelands (shown in light and dark green) are located in the mountains and valleys around dáɁaw (Lake Tahoe), along what is now the California-Nevada border. Today, most Wá∙šiw people live in colonies and communities of the Carson Valley of Nevada (shown in black).

Credit: Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California.

HÍMU IN WÁ∙ŠIW WEAVING

hímu, particularly the willow that grows in the valleys around the Lake Tahoe region (“valley hímu,” also known as coyote willow) is especially important to Wá∙šiw basket weaving for tradition and quality material. Baskets can be woven from most materials, but quality Wá∙šiw basketry wants and sometimes requires strong valley hímu for its strength and clean color.

Healthy valley hímu can grow long stalks independently, but human encouragement is the traditional way. Traditional growth patterns were propagated by planting hímu, pruning them, having fire consume or interact with them, shaping them to provide shade from hot sun-filled days, and more. The continued handling leads the plant to grow long and strong.

“My great aunts, the Smokey Sisters, and other elder basket weavers like Marie Kizer and Florine Conway, harvested and tended to the willow in Dresslerville along the river and surrounding areas,” said Melanie Smokey, Wá∙šiw basket weaver. “They would talk to the willow and were proud of this area. They graciously accepted visitors who asked to harvest willow in the area. Once everyone gathered their bounty, then they would all go to the Senior Center where a pre-planned good meal was served in honor of the guests. They were proud of their Wá∙šiw má∙š, their lands. Their baskets didn’t just hang on a wall, their baskets were used to gather, to sift pinenut and acorn flour in, and to cook in. They wanted basketry to continue so they taught and encouraged young people.”

Without the human touch, knots, bends, and eyes (from buds of branches) can become common. These become hindrances for collection of the long stalks that are necessary for a strong product and create weaknesses in the weaving.

Valley hímu has become the main variant of willow used for weaving, despite other types being readily available, because of the ability to grow tall and straight. These willows create the structure of the basket. hímu that grows in the mountains (“mountain hímu”) grows low and bunched, providing shorter stalks that make for weaker baskets, which last for one season at most.

Mountain hímu that grows in the Tahoe Basin has been used for fishing traps or twine, and temporary burden baskets, explained Smokey. The hímu in Northern Nevada’s arid low valleys is stronger, straighter, and necessary for complete and keepable baskets.

The long stalks of valley hímu create baskets of maximum strength that hold together under use of fire for roasting or carrying heavy objects for years. The feeling and fact of strength from valley hímu is most apparent in baby boards, which carry the next generation, make the child feel safe, and last for decades.

A ~100 year old Wá∙šiw hímu burden basket that was used over 2 lifetimes. Basket was on display as part of Wa She Shu It’ Deh at Meeks Bay, courtesy of Melba Rakow.

Credit: Robin Smuda.

VALLEY HÍMU IN DECLINE: DROUGHT, HEAT, FIRE, AND MORE

Valley hímu on Wá∙šiw lands are under stress from drought and heat. hímu that is tall and healthy enough for weaving is practically nonexistent in the wild in Carson Valley, according to local weavers. Wá∙šiw weavers have harvested usable stalks in limited amounts from the Nature Conservancy preserve at River Fork Ranch in the Carson Valley, but finding quality hímu in other areas is so difficult that gatherers protect locations from many people out of respect, for the land is not a guarantee.

“…my cousin Sue goes clear to Oregon to get hers because this lady grows it for her in her yard,” says Melba Rakow, Wá∙šiw Elder and employee of the Culture and Language Resources Department of the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California.

In addition to drought and heat, the unnaturally long and powerful fires from years of current forest management practices and climate change harm valley hímu as they tear through the landscape. hímu is burned down, damaged, or in some cases preemptively destroyed with herbicide as they are seen as an agricultural weed and potential fire hazard.

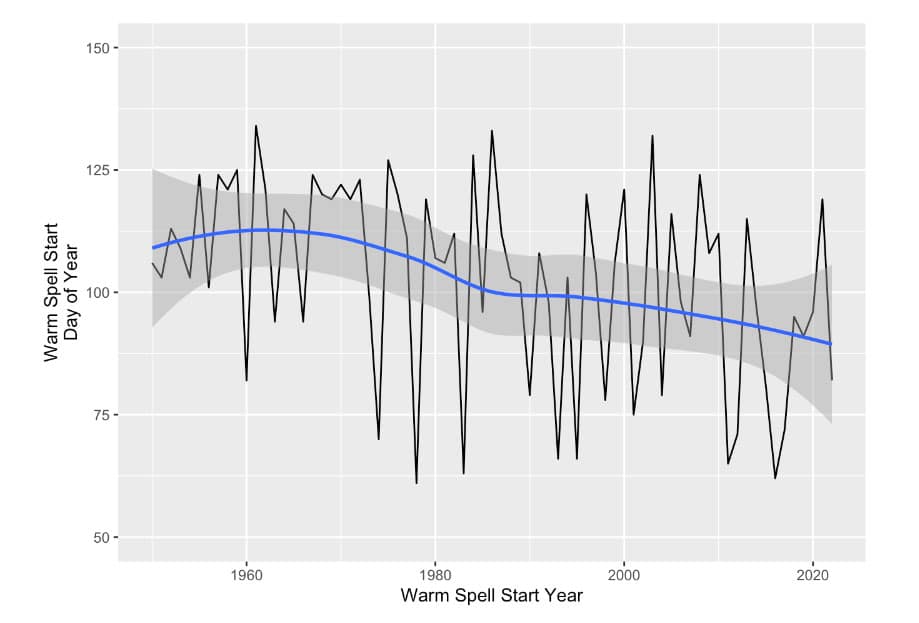

Changes in the timing of the warm season may also be impacting the timing of hímu flowering. Wá∙šiw weavers have noticed that the timing of flowering is becoming more unpredictable. Analysis of weather data by Paige Johnson and Kyle Bocinsky from the Native Climate team found that in Minden, Nev., the first warm spell of the year (measured as 7 consecutive days where the minimum daily temperature rose above 28oF) has been happening earlier in the year. Their data shows that the first warm spell is occurring about 2.8 days earlier every decade, which amounts to nearly 3 weeks over the last 70 years.

The earliest 7-day warm spells recorded each year at a weather station in Minden, Nev.

Credit: Paige Johnson and Kyle Bocinsky, Native Climate.

INTERACTION, NOT EXPLOITATION

Some of the problems facing Wá∙šiw today are the ability to restart traditional valley hímu growing practices and access to land, water, and money needed to propagate them. Many of the best areas for hímu growing are controlled by resource production and natural conservation mindsets. Most parks and natural areas in the Carson Valley are designed to keep nature in its pure state. Ranches that surround the Carson River and lusher areas of the Carson Valley are focused on livestock production and control large areas of land and water.

Working and living with the land gets us to a healthier environment, says Herman Filmore, Director of Culture/Language Resources Department of the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California. The plants and land are sovereign beings, and we live with them, which includes human interaction and use. He explains that the idea of untamed wilderness Indigenous peoples lived in is detrimentally wrong. Plants were harvested and propagated on purpose. Landscapes were managed and areas were cleared. The difference is that human needs were not the only concerns.

Campsites were used and plants were cared for, but not always, as rest is important for the plants and the landscape, says Rakow. The overworking of land is something she has seen in her life. Ranchers in the Carson Valley used to have cattle graze one area and let that area heal for years before using the land again. Today, this is much less common.

Valley hímu growth near an unkept creek. Note that the majority of the branches are broken or twisted and unusable for weaving.

Credit: Robin Smuda.

A RETURN TO TRADITIONAL WAYS

These are long-standing problems, but solutions are underway. For the first time in a generation, valley hímu is now being worked with on Wá∙šiw land in mass. It is a return and reimagining of what was done before. Rhiana Jones and the Washoe Tribe’s Environmental Department have been working on a pilot project to grow hímu that will be accessible to the whole community. She and others have propagated hímu stalks on the Dresslerville Reservation in the Carson Valley using traditional methods of fire and pruning to encourage great-quality stalks.

While efforts to have valley hímu in our community again are growing stronger, much still needs to be done in order to restore our relationship with this plant and the landscape as a whole. hímu faces many of the same challenges that we do — less water, intense heat, destruction of the environment, and out-of-control fire. They are resilient, as they always have been. It falls on people to become reconnected and move forward with them for generations to come.

hímu cradle boards, 3 used roasting pans, lidded baskets, and a traditionally made cedar net on display at Wa She Shu It’ Deh at Meeks Bay courtesy of the Culture and Language Resources Department of the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California.

Credit: Robin Smuda.

Robin Smuda is a Wašiw person and a member of the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California. Currently, they are a reporter intern with Native Climate at DRI and studying Cultural Anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno. Robin is planning on studying Ethno-Archeology and Indigenous Studies in grad school, with a focus on the transition from pre- and post-contact in the Great Basin.