Reno, Nev. (Nov. 28, 2018): This week, new research on historical climate changes in the Earth’s polar regions by an international team of scientists was published in the journal Nature. The study, titled “Abrupt Ice Age Shifts in Southern Westerlies and Antarctic Climate Forced from the North,” is underpinned by data provided by Joe McConnell, Ph.D., director of DRI’s Ultra-Trace Chemistry Laboratory in Reno, Nev.

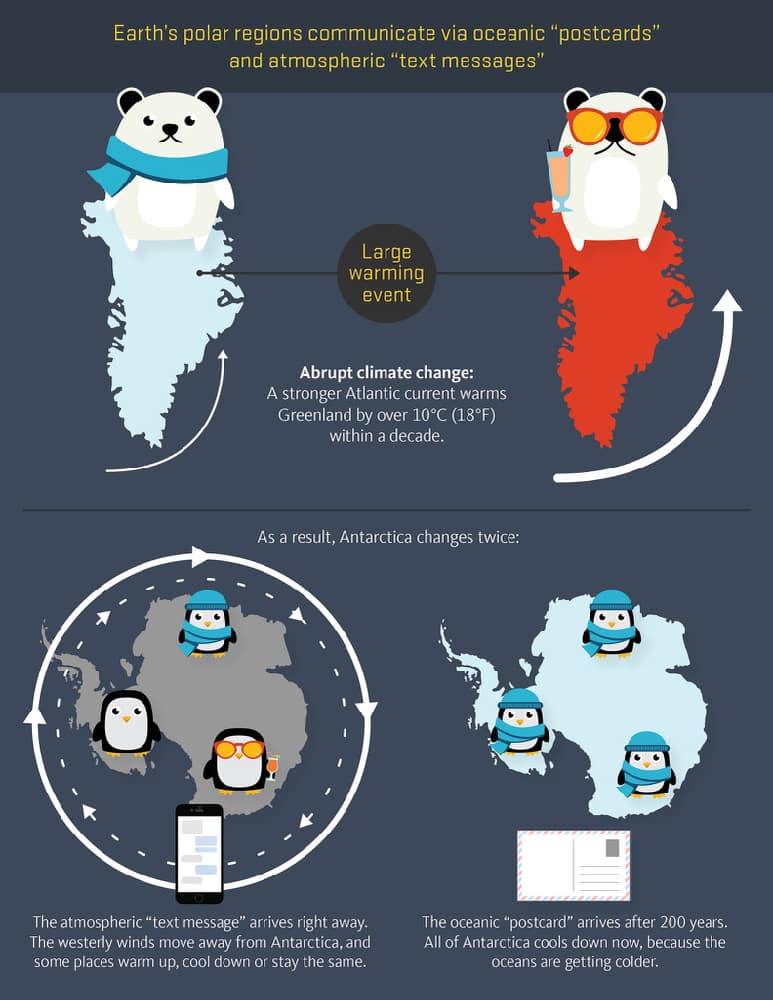

The recently published study explains the interconnection between Arctic and Antarctic climates, tracing how strong currents in the North Atlantic during the Ice Age forced Southern Hemisphere climate on two different timescales: first, by rapidly warming Greenland and triggering immediate atmospheric changes in Antarctica due to shifting wind patterns, and second, by cooling the continent via colder ocean temperatures two centuries later. Researchers liken the atmospheric climate change in the North Atlantic to a “text message,” delivered immediately to the Southern Hemisphere, while the oceanic cooling is more like a “postcard,” not felt in Antarctica for another 200 years.

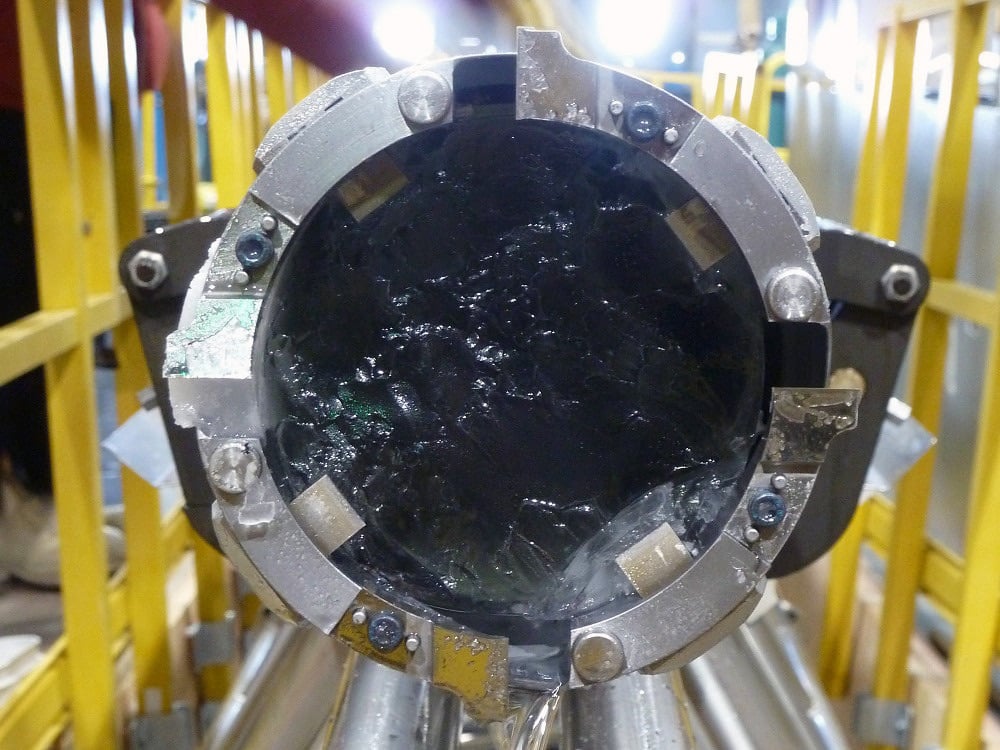

To identify this climate “teleconnection” between Earth’s poles, researchers relied on detailed chemical analyses of more than 1.5 km of Antarctic ice core, including more than 400,000 individual measurements, made in the Ultra-Trace Chemistry Laboratory using a unique continuous flow system and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Retrieved from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), this ice core sample, known as the WAIS Divide core, was collected by a team including DRI emeritus research professor Kendrick Taylor, Ph.D. Their original research into the connection between the Earth’s polar regions using the WAIS Divide core was first explained in Nature in 2015.

The full text of the study titled “Abrupt ice-age shifts in southern westerly winds and Antarctic climate forced from the north” is available in Nature: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0727-5. A full news release from Oregon State University is below.

The final drill run of the WAIS Divide ice core, with ice from 3,405 m (11,171 ft) depth that has been buried for 68,000 years. Credit: Kristina Slawny.

Study: Earth’s polar regions communicate via oceanic “postcards,” atmospheric “text messages”

By Mark Floyd, 541-737-0788, mark.floyd@oregonstate.edu; Sources: Christo Buizert, 541-737-1572, buizertc@science.oregonstate.edu; Justin Wettstein, 541-737-5177, justinw@coas.oregonstate.edu

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Scientists have documented a two-part climatic connection between the North Atlantic Ocean and Antarctica, a fast atmospheric channel and a much slower oceanic one, that caused rapid changes in climate during the last ice age – and may again.

In a new study published this week in Nature, an international team of scientists

The new research documents how the North Atlantic communicates these extreme events to Antarctica, at the opposite side of the world.

“The North Atlantic is sending messages to Antarctica on two different time scales,” said Christo Buizert, an Oregon State University climate change specialist and lead author on the study. “The atmospheric connection is like a text message that arrives right away, while the oceanic one is more like a postcard that takes its time getting there – in this case, 200 years, which makes the postal service look pretty good by comparison.

“When the North Atlantic warms because of the strengthened AMOC, all of Antarctica eventually will cool because of oceanic changes. It begins with the winds, but the ocean delivers a much bigger impact two centuries later.”

Credit: Oliver Day, Oregon State University.

During the last ice

Global atmospheric conditions changed immediately and westerly winds blowing around Antarctica shifted away from the land, which caused warming in some parts of Antarctica and cooling in others. The second half of the impact was much slower, a cooling effect of the southern hemisphere oceans that didn’t manifest itself in Antarctica for 200 years.

The study explains why the climate in Greenland and Antarctica have not exactly aligned over time, according to Oregon State atmospheric scientist Justin Wettstein, a co-author on the study.

“This is the first time that you can so clearly see the nuts and bolts of how the climate works on time scales much longer than our meteorological observations,” Wettstein said. “It allows us to see how Greenland and Antarctica have been connected – spatially and temporally – long before people were running around with thermometers to measure the temperature.

To reconstruct the climate, the researchers examined ice cores from five different locations in Antarctica and synchronized the dates by looking at layers of volcanic ash. They measured changes in the temperature by analyzing ratios of water isotopes. They then matched the data with well-established dates of the so-called “Dansgaard-Oeschger” events in Greenland ice cores to pinpoint the connection between the hemispheres.

These extremely abrupt events happened roughly 25 times during the last ice age, from 100,000 to 20,000 years ago, the researchers say.

“When the Gulf Stream switches on to full strength, Greenland can warm as much as 10 to 15 degrees Celsius within a decade,” Buizert said. “The change is abrupt and massive. As the ocean transfers heat to the north, the rest of the global ocean starts to cool down. Antarctica eventually ‘notices’ the oceans getting colder, but only after 200 years have passed.

The atmospheric shift in Antarctica’s past has a certain pattern of where it is warmer and where it is colder – a kind of temperature fingerprint, Buizert said.

“What is really neat is that by looking at modern-day observational data we can find an

Observational data and climate models show that the AMOC current today is weakening because of global climate change, thus what happened during the last ice age could happen again.

The researchers say that if the past is a guide for what the future may hold, the weakening of the AMOC likely will decrease the potency of Asian monsoons and billions of people depend on that rain for their livelihood. The changing wind patterns in the southern hemisphere also will lessen the ocean’s ability to take up carbon dioxide, meaning more CO2 emissions will stay in the atmosphere, strengthening the greenhouse effect.

“We know that our world is now warming on average, but the regional changes depend also on how the atmospheric and oceanic circulations respond,” Wettstein said, “and that is something that climate models still disagree on. This study gives us a real-world example of past circulation change that we can use to test and improve our models.”

The researchers caution that other influences besides the AMOC also will affect climate change – rising temperatures from greenhouse gases are a major factor globally, and changes to the ozone layer affect wind patterns and climate in Antarctica.

Buizert, who has been on scientific expeditions to Antarctica and Greenland multiple times, said the research is “really exciting for climate geeks like us to figure out how the pieces of our climate are connected.”

“The findings also may have implications for the future,” he noted. “The AMOC is weakening now because of global warming and meltwater from Greenland. The ‘text message’ is being sent and atmospheric conditions are changing. The ‘postcard’ is on the way.”

The study was supported by the National Science Foundation and other sources. Authors on the study were from the U.S., Switzerland, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Australia, Japan

Buizert and Wettstein are in OSU’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences.

The Desert Research Institute (DRI) is a recognized world leader in basic and applied interdisciplinary research. Committed to scientific excellence and integrity, DRI faculty, students, and staff have developed scientific knowledge and innovative technologies in research projects around the globe. Since 1959, DRI’s research has advanced scientific knowledge, supported Nevada’s diversifying economy, provided science-based educational opportunities, and informed policy makers, business leaders, and community members. With campuses in Reno and Las Vegas, DRI serves as the non-profit research arm of the Nevada System of Higher Education.

Northern Nevada Science Center

2215 Raggio Parkway

Reno, Nevada 89512

PHONE: 775-673-7300

Southern Nevada Science Center

755 East Flamingo Road

Las Vegas, Nevada 89119

PHONE: 702-862-5400