Wildfires in the Western U.S. are getting bigger, with real consequences for the air we breathe. In 2018, the Martin Fire burned through northern Nevada — the largest fire in the state’s history. The same year, smoke from California’s Mendocino Complex fire choked Nevada’s skies, followed by another six wildfires throughout 2020 and 2021, all of which comprise the largest wildfires in California history. As these wildfires burned, most of rural Nevada lacked the air quality monitoring needed to understand how public health risks were changing from one day to the next. In 2021, DRI researchers partnered with the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection (NDEP) to address this gap. Led by Kristin VanderMolen, Ph.D., assistant research professor of atmospheric science, a new study details how the research team designed custom air quality sensors and information materials for rural Nevada counties. The air quality information is now publicly available on the NDEP website. Fortunately, recent years have experienced far fewer smoky days, and the team is now waiting to test their materials during the next large wildfire. large wildfire.

Below is a Q&A with VanderMolen about the study, how the project will help rural Nevada communities, and the collaborative value of working other DRI scientists. The interview is edited for length and clarity.

DRI: What inspired this study?

VanderMolen: The motivation for this project came from the scarcity of air quality monitoring and related information resources in the rural counties of Nevada. Starting in the late 2010s, emergency managers in some of the rural counties began inquiring with NDEP about whether and how they could obtain air quality monitors. When we became aware of those inquiries, we teamed up with NDEP and applied for funding from the EPA to expand the air quality monitoring network in rural Nevada using custom air quality monitoring packages. We also wanted to provide emergency managers and other officials in the rural counties with information resources so that we weren’t just generating air quality data by way of the monitoring, but also making sure that people had support for interpreting and making use of the data if they chose to do so.

The findings in this publication went into our development of information resources about wildfire smoke risk and exposure mitigation for our partners on the project, which include the Office of Emergency Management in Storey County, the Office of Emergency Management in Pershing County, and the National Weather Service Office in Elko. They’re really the entities that are ultimately interacting with the public.

DRI: How many new air quality monitors are there because of this project and where?

VanderMolen: There are three monitoring stations in Storey County, four in Pershing County, and four in Elko County. So, 11 new monitoring stations in total are up and running, and NDEP created a website where the information can be accessed.

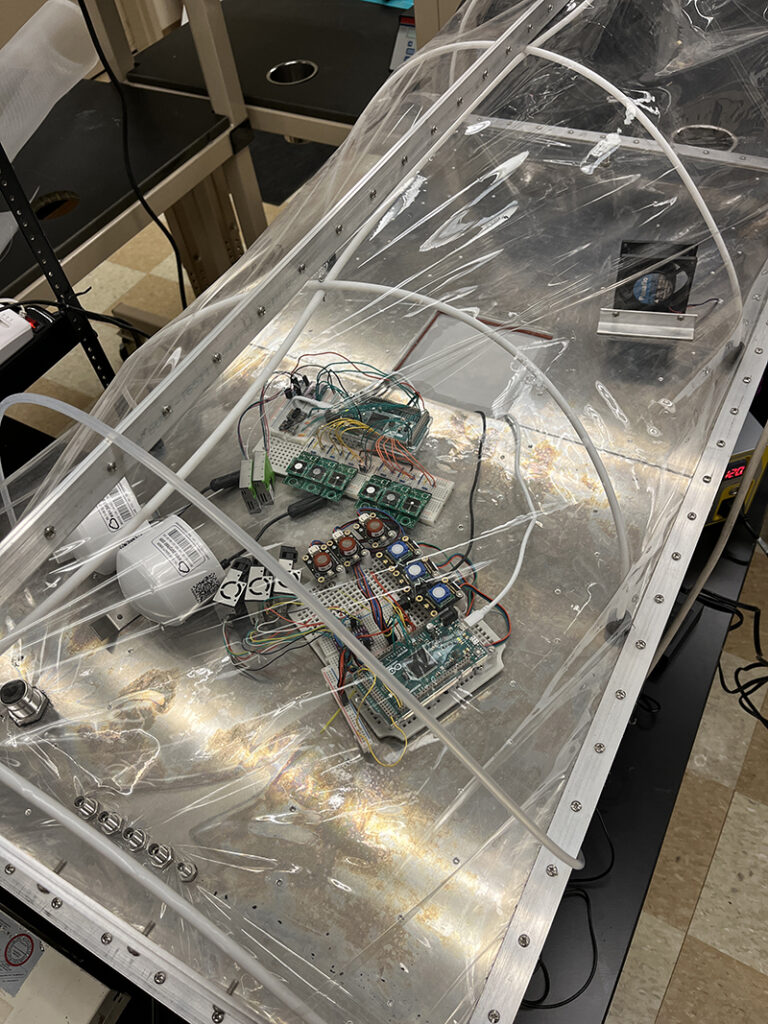

We initially developed the custom sensor packages following lab testing of individual sensors and have since been testing the packages by comparing the performance to nearby EPA regulatory monitors. Since we haven’t had much wildfire smoke in recent years, we’re still waiting to test them during a smoky year.

DRI: How do you think this study adds to scientific and/or local understanding of the issue?

VanderMolen: In terms of local understanding of the issue, it identifies what aspects of wildfire smoke risk and exposure mitigation people are already aware of, and what aspects of those topics they may be less familiar with. By understanding what people are aware of, it provides an opportunity for officials like emergency managers and the National Weather Service to reinforce that knowledge in local populations. By understanding what people are less familiar with, it provides an opportunity for them to work toward enhancing the current knowledge base.

In terms of scientific understanding, the contribution is really in the realm of applied research. Information needs among rural publics related to wildfire smoke risk and exposure mitigation are not particularly well known. A lot of the research on information needs has been focused on populations that are considered easier to reach — there’s still a pretty big need to focus also on populations that are harder to reach, including rural populations or communities for which English is not the primary language spoken.

DRI: You use mental models for this purpose in the study. Can you talk about what this means and how it worked?

VanderMolen: Mental models are used in risk communication research to identify what aspects of a particular hazard people are already aware of and what aspects of it they are less familiar with. You create two models: one is the specialist model, which reflects how specialists in the field conceptualize and understand the topic, and that’s created through literature review. You also create a non-specialist model that reflects how the public conceptualizes and understands that same topic, which we created through interviews and a questionnaire. The idea is that you can then overlay the two models to quickly identify similarities and differences in how those two groups conceptualize and understand the topic. So in our case, it enabled us to quickly identify important points related to wildfire smoke risk and exposure mitigation that specialists have focused on but non-specialists have not. It also allowed us to identify points that are important to non-specialists that are not in the purview of specialists. So, it works both ways.

Overall, it’s meant to be a tool that enables you to quickly identify the similarities and differences, and then you can dive deeper into those areas to inform the development of risk communication materials.

DRI: Did anything about your findings surprise you?

VanderMolen: I don’t think so, in that rural counties in Nevada have been so heavily impacted by wildfire smoke, particularly in 2020 and 2021, that they have a lot of experience with it. So we found that there is a strong experiential knowledge base but also various ways to complement it.

DRI: Can you talk about the infographics designed for this study?

VanderMolen: We produced two different sets of infographics. In one set, there’s one infographic corresponding to each AQI (Air Quality Index) category that is heavily color coded to try to help people who are not accustomed to looking at AQI categories to become familiar with them. The idea is that, for example, if an emergency manager sees that the air quality is unhealthy for sensitive groups, they can push out the “unhealthy for sensitive groups” infographic. Each of those infographics provides very basic outdoor guidance for different groups including healthy adults, those who are sensitive to wildfire smoke, and outdoor workers. The second set of infographics touches on different essential concepts, like which groups are more at risk and how to select a good portable indoor air cleaner.

At the request of one partner, we also made enlarged, printed, laminated copies of the infographics that could be shared with rural health centers. The idea is that rural health center staff can hop online, see what the AQI is, and then post the corresponding infographic in the reception area to communicate to people as they’re coming in, “the air quality is moderate today.” It’s a way to start a conversation around wildfire smoke and help inform people. At the request of another partner, we made hanging AQI wall dials with a moveable arrow for use in public places like libraries, senior centers, and town halls. Together, these resources provide air quality information to people who are not online. We also created a data interpretation guide that is meant to be of use primarily by our partners but that people like senior center staff can also reference to help answer questions they may get from the public.

DRI: When will the materials be ready to share with the public?

VanderMolen: All of the infographics underwent extensive evaluation during their development and are now ready to be tested during a wildfire smoke event. Same with the data interpretation guide. We had anticipated having them finalized by now, but we haven’t had much wildfire smoke lately, so we’re still waiting. If it’s a smoky summer, then we’ll be testing everything on the project including the actual sensor packages, in terms of their performance, and then finalizing all of the information materials in the fall.

DRI: Can you talk a little bit about the number of direct, DRI collaborators on the project and the value that everyone brought?

VanderMolen: There’s myself, Yeongkwon Son, Meghan Collins, Tamara Wall, Greg McCurdy, Pam Lacy, Rebekah Stevenson, Nick Kimutis, and Lori Fulton.

Yeong and Greg’s shared expertise in environmental monitoring has been critical, because together they built the custom sensor packages. Yeong’s expertise in exposure science and public health has also been critical to the development of the specialist mental model, the data interpretation guide, and to the review of the information materials. Greg, with significant support from Pam and Rebekah, was also key to getting the air quality data from DRI to NDEP, because it is made publicly available through their website, not through ours. And that has to do with the fact that NDEP is in a position to give longevity to this project.

Tamara’s role has been one of mentor to the group, to help provide guidance and troubleshoot. Meghan’s role has been primarily in developing content for the information materials, drawing on her background and expertise in science communication, and in contributing to the development of the mental models.

Nick, who was an MPH student at the time at UNR, helped with the literature review that informed the specialist model. We were lucky to have a student within the WRCC who was familiar with climate-related hazards but then also, coincidentally, working towards an MPH degree with a focus on epidemiology. Lori provided essential input on and completed the design of the infographics, other information materials, and data interpretation guide.

DRI: And outside of DRI, who are your collaborators and partners?

VanderMolen: NDEP is our collaborator, and then our partners are the Office of Emergency Management in Storey County, the Office of Emergency Management in Pershing County, and the National Weather Service Office in Elko.

DRI: Where will the project go from here?

VanderMolen: The final stage will be during an actual wildfire smoke event, when we’ll look at how the custom sensor packages perform alongside the reference sites. The data interpretation guide will be evaluated through regular interaction with our partners in the rural counties, checking in with them to understand whether and how they’re using it, whether and how it’s meeting their specific needs, and how it can be improved. Katherine Lambrecht, a rhetorician who is now at Arizona State University but was previously at UNR and DRI, is going to do a rhetorical analysis of public responses to the infographics as our partners push them out. We’ll also be working with students to observe and inquire into the use and effectiveness of the tangible information resources.

Ultimately, this is kind of a pilot project. Now that we’ve developed the sensor packages and the information materials, the idea is that NDEP will house those products and the knowledge for their replication in the idea that other rural counties in Nevada might adopt them as well. That’s the end goal.