Lynn Fenstermaker, Ph.D., recently retired from DRI after 32 years. Throughout her career as an ecologist and remote sensing scientist, she tackled large-scale questions about environmental stressors, including the impacts of climate change and wildfires on Great Basin and Mojave Desert ecosystems.

Her long list of career achievements includes serving as Director of the Nevada Space Grant Consortium and Nevada NASA EPSCoR, as well as two statewide research programs examining the effects of climate change: the Nevada Desert FACE Facility (NDFF) and the Mojave Global Change Facility (MGCF). She also acted as Director of the Nevada Climate-ecohydrological Assessment Network (NevCAN). Fenstermaker served on three national boards (National Space Grant Foundation, National Space Grant Council Executive Committee, and NASA EPSCoR Caucus) and a state board that governs the Nevada Institute for Autonomous Systems. At DRI, she served as Deputy Director of the Division of Earth and Ecosystem Sciences.

Fenstermaker – who was recently admitted to her high school’s hall of fame – shared some of the biggest projects of her career, plans for retirement, and the advice she would give to young scientists following in her footsteps.

Fenstermaker (with Eric Knight, UNLV) collecting multi-spectral images with UAS.

Credit: Lynn Fenstermaker/DRI.

DRI: What first brought you to DRI?

Fenstermaker: When I first came to Las Vegas, I had just wrapped up all but the writing for my master’s degree in agronomy at the Pennsylvania State University. I took a job with the EPA’s Remote Sensing Lab, where I got involved in a lot of projects all across the country, from Montana down through Nevada. (Note: Fenstermaker worked on the EPA’s first ever GIS project, which modeled groundwater contaminant plumes to identify the sources of contamination. This project helped demonstrate how GIS could produce useful information for the EPA).

After I finished my master’s in 1986, I moved to Las Vegas to take a job at Lockheed, where I worked for a little over two years. While I was there, I got to know the director of the Environmental Research Center at UNLV and worked there for three years. When I decided to leave, I created my position at DRI, which was initiating a cooperative agreement with the EPA lab here in Las Vegas. So, I said “Hey, I would like to do this work, but I’d like to do it in collaboration with the other remote sensing scientists at DRI.” The EPA said yes, so I sort of created my own position.

I’ve been at DRI ever since, and that’s been 32 years. Which doesn’t seem possible because I’m still young on the inside.

Fenstermaker’s nearly all-female PSU team competing at the National Soil Judging Contest in Nebraska. Fenstermaker is second from the right.

Credit: Lynn Fenstermaker/DRI.

DRI: What encouraged you to stay at DRI for so many years?

Fenstermaker: I like the flexibility of being able to take on different projects. Everyone who’s been at DRI for some length of time knows that funding can be challenging – there were times when I scrambled for funding, particularly when we lost the cooperative agreement with the EPA lab. It was at that time that I decided to go for my Ph.D., so I was working full time in a soft money environment, keeping myself fully funded, taking classes, and working on a dissertation – It took me 11 years to finish my Ph.D.

After my Ph.D. I thought about going to a university to teach and do research while having a hardwired salary. But then I talked with faculty about all the university stressors, and I thought, “Well, at DRI there’s only one big stressor – and that’s keeping yourself funded.” So, I networked a lot, and I think having a collaborative spirit really helped me to get involved in various projects, as well as my organizational skills.

DRI: Tell me about the NevCAN project.

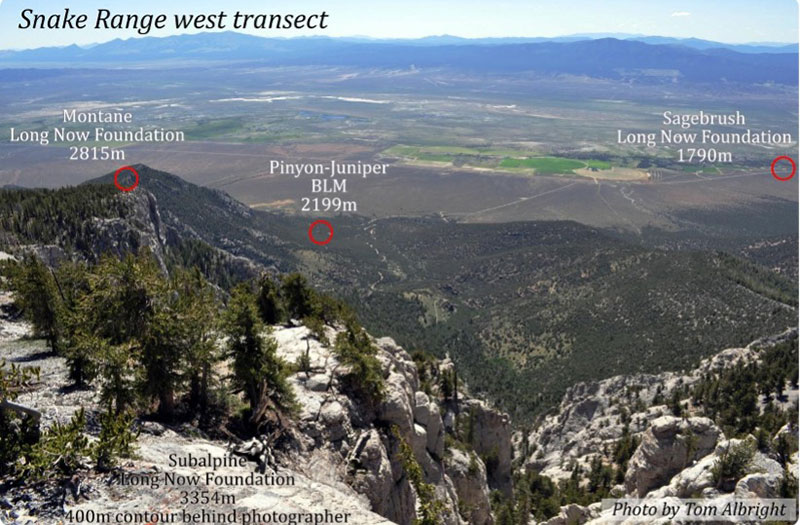

Fenstermaker: NevCAN’s goals were to develop standardized infrastructure with real time data collection to measure and analyze the effects of climate variability and change on ecosystems and disturbance regimes. We also wanted to better quantify and model changes in water balance and supply under climate change.

Essentially, it’s a series of meteorological stations with common sensors across two mountain ranges in Nevada. The stations are centered within each ecosystem type. And we’re looking at weather variability and climate at different elevations.

We measure incoming solar radiation (long and shortwave), and incoming precipitation, as well as factors that affect that including wind speed, wind direction, and air temperature at different heights. We also measure soil moisture and soil temperature, and within vegetation, we measure the fate of the water: how much is transpired from trees or evaporated from the soil surface, how much went into deep leaching and potentially could enter the groundwater at some point in time.

Unfortunately, when you’re looking at climate variability and change, you can’t just measure for five years and say, voila – no, it’s long-term monitoring. And a lot of the federal agencies don’t want to pay for long term monitoring.

NevCAN transect locations in Nevada’s Snake Range.

Credit: Lynn Fenstermaker/DRI.

DRI: Can you describe some of your other large projects, the Desert FACE Facility, and the Mojave Global Change Facility?

Fenstermaker: The Desert FACE facility fumigated an intact ecosystem with elevated CO2 to determine plant and ecosystem response to the increased CO2. We published a Nature paper in 2014 that was pretty much a summary of the project data. What was interesting about this is that overall, we saw retention of carbon in the soil, not in the plant matter.

The Mojave Global Change Facility looked at what would happen with soil disturbance, nitrogen deposition and increased summer monsoon precipitation. Because earlier climate models predicted an increase in summer rain in the Mojave Desert due to global warming, we simulated increased summer precipitation. The models have since changed, and both the models and weather data clearly show that this isn’t the case. Monsoon flow is not bringing more summer precipitation into the Mojave Desert.

We’re maintaining both sites for future research, because they’re really unique, one-of-a-kind research sites in the world.

Fenstermaker hand-digging holes for rain gauges at the Mojave Global Change Facility.

Credit: Lynn Fenstermaker/DRI.

DRI: Tell me more about your work as the Director of Nevada NASA EPSCoR.

Fenstermaker: EPSCoR is the Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research. It’s a program funded by Congress for states who receive less than 0.75% of all NSF research dollars, or less than 10% of all federal research dollars.

The history of this program is interesting. During World War II, there was a lot of buildup along the coasts of the United States. And a lot of industry was concentrating in these regions, and as universities started partnering with industry to build their programs, they got a lot of research dollars. Additionally, most of the NASA centers are located along the coast. There are only a few that are quasi- interior, like Glenn Research Center in Ohio, but the rest are in Virginia, Texas, California, and Louisiana. This is why the interior states largely got left behind. EPSCoR is a way of spreading out the funding to the interior states who do not have those industry collaborations or that rich history of developing unique research infrastructure capabilities. The states that primarily benefit are Nevada, New Mexico, Wyoming, Idaho, Missouri, Mississippi, South Carolina, Alaska, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Vermont, and New Hampshire. The Nevada Desert FACE facility was a DOE EPSCoR project.

Fenstermaker served as the Director of Nevada NASA EPSCoR and the Nevada Space Grant Consortium.

Credit: Lynn Fenstermaker/DRI.

DRI: You also served as Director of the Nevada Space Grant Consortium. Can you talk a little about that?

Fenstermaker: NASA requires that in EPSCoR states, whoever is the Space Grant director also serves as that state’s NASA EPSCoR director. Space Grant is all about improving STEM education, so we run solicitations and review panels to make sub awards to Nevada faculty and students. Some of the most important solicitations we do are undergraduate research scholarships, graduate student fellowships, and student internships at NASA centers.

I convene a faculty review panel of at least three members, each one from a different Nevada System of Higher Education institution, to review all of the applications, then convene the panel and make the selection for who receives funding. I do the same for faculty awards. On the Space Grant side, we fund faculty to improve higher education or pre-college education. For both of those we have a hands-on training component for either college students or pre-college students. One of the successful programs has been a program where a UNR faculty member mentors at an engineering high school in Reno, and they build a human-powered rover to take to Huntsville, Alabama, to participate in national competitions. And every time they’ve gone, they’ve won one or more awards.

On the pre-college side, in addition to the hands-on training for students, we also fund teacher training. The DRI Science Alive team has been quite successful at applying for these funds.

So, I oversee all of that, and go to the national meetings: I’ve served on the National Space Grant Council Executive Committee, which is the group of directors from across the country that connects the Space Grant program to NASA’s Office of STEM Engagement. I’m handing over the role of Secretary of that Committee to Eric Wilcox, the incoming NV Space Grant and NV NASA EPSCoR Director.

DRI: What are your plans for retirement?

Fenstermaker: I’m going to exercise more, and I’ll continue to work part time. I’m going to try to wrap up things with NevCAN and with the Desert FACE and Mojave Global Change Facilities so they can remain intact and be passed forward.

I also started watercolor painting a couple of years ago, which is fun. And I’ll keep hiking and bicycling. Basically, I’ll be figuring out this transition as it happens.

DRI: What advice do you have for young researchers or young climate change scientists?

Fenstermaker: Not to have too high of expectations — I always compared myself with people that were putting out 200+ publications over the course of their career, and that’s just not who I am. It’s important to learn who you are and accept yourself, recognize your strengths, as well as where to challenge yourself — and to network. Communication is critical.

Don’t strive for perfection, or you’ll really disappoint yourself or fall behind. Just strive to meet your obligations and do it reasonably well. Also, you’ve got to schedule personal time, as well as work time. For example, if you’re going to a conference in a cool area, schedule a couple of days before or after and do a little sightseeing, take a significant other with you and make time for family and yourself so that you don’t burn out.

A young Lynn Fenstermaker presented 4-H projects on soil conservation, geology, fossils, and insects.

Credit: Lynn Fenstermaker/DRI.

DRI: Is there anything else you think is important?

Fenstermaker: A few more words of wisdom: Watch for windows of opportunity, because a lot of things I got involved in came from communicating with people who opened a window of opportunity for me, and I said yes.

Overall, DRI has been a great place to work, particularly at the Southern Nevada Sciences Center. It feels like family. It’s a great organization because you have the flexibility to go in a lot of different directions with your research, and work collaboratively across disciplines and across institutions, which is really rewarding.