Benjamin Hatchett, Ph.D., is an assistant research professor in the Division of Atmospheric Sciences at the Desert Research Institute in Reno. Ben has been a member of the DRI community since 2005 when he began as an undergraduate lab assistant. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in geography, Master’s in atmospheric sciences, and Ph.D. in geography, all from the University of Nevada, Reno. Ben specializes in dryland and alpine hydroclimatology and hydrometeorology. In addition to his research and teaching, he enjoys watching the sunrise with a cup of coffee before going backcountry skiing, climbing, or mountain biking in the Sierra Nevada.

DRI: You’ve been in Reno for some time now. Could you tell us about what brought you to Reno originally and your educational background?

BH: I came to the University of Nevada as an undergraduate. I was always planning on going to Montana State, but I grew up snowboarding on Donner Summit, and friends and I would ride Boreal for the night sessions. I remember riding there one night, in the evening when the sun was setting and everything was purple and pink in alpenglow, and I thought, I just can’t leave. This is where I’m from, and this is what I do, and I want to keep doing this. And I can go to school right down the street from here. Perfect! So, that’s what brought me to UNR.

During my time as an undergrad, I took the full sequence of avalanche safety courses because I’d gotten really into being in the backcountry. Those courses started convincing me that I needed to learn more about meteorology, then I spent a summer in Chamonix, which reinforced that idea. Skiing in the Alps, in an environment so different than the Sierra Nevada with huge glaciers and extreme hazards, and seeing how fast the weather changed there, made me realize that I really needed to learn more about weather and its relationship to snow science.

DRI: Now you do quite a bit of work related to avalanches. What does that research involve, and what are the big questions?

BH: My goal is to better apply what we know about meteorology to understand the timescales and prediction skill for avalanches and how we can use that to minimize risk. Subtle changes in weather, like wind direction or snow crystal shape, can quickly create massive changes in the safety of a slope and the state of a given snowpack. As soon as you want to apply what you know about snow to understand its relation to the mountain environment, you need meteorology so you can say, for example, this is the sort of storm that can create large and widespread avalanche activity, thus we’ll need extra patrollers at the resorts.

For me, it all comes from the question: where’s the best safe place to ski and why? So much of my work is seeing something interesting while I’m in the mountains and thinking “I wonder why that happened?” For example, why did that slope slide when another didn’t? How does that tie into the meteorological history of the snow season?

A skier poses on the massive pile of snow and debris left behind by the Valentine’s Day 2019 avalanche on Mt. Shasta. Credit: Ben Hatchett.

DRI: Can you tell us about one of those times you saw something interesting out in the field and investigated it?

BH: Probably the best recent example I have is the avalanche that took place on Valentine’s Day 2019 on Mt. Shasta. In late June of last year, we skied up what was left after the avalanche, a fifty-foot-tall pile of debris. Skiing up it and seeing the remnants many months later was really striking and made me want to look further into it.

The big question that folks in my field were speculating about was when it happened, because that can tell us a lot about why it happened. I thought of checking the seismic network to see if it would have registered there, and sure enough, it did! This allowed us to pinpoint the time of the slide to the second it occurred. From there, we could evaluate all the other information we typically look at, like wind speed and direction, precipitation phase, and temperature, and begin to make more-informed hypotheses about what caused the avalanche.

DRI: Have you seen that snowpacks, and the potential for avalanches, are changing under warming climate conditions?

BH: Climates have always changed, but what we’re seeing now across mountain landscapes is something different. We have background warming, which is causing more precipitation to fall as rain instead of snow in middle and lower elevation mountains. This warming is also causing fewer freezing nights in the spring, which goofs up our historically awesome spring skiing. We’re seeing more extreme loading events, with lots of snow falling all at once, but also more prolonged (and warmer) dry spells. High elevation rain-on-snow events are becoming more frequent, which creates an unstable surface for additional snowfall once they freeze. All of this favors weaker snowpacks, which suggests more, and larger, avalanches may be possible.

I’m working on an article right now related to this and the future of skiing. As lower elevation snowpacks disappear, more skiers and snowboarders are pushed into the higher elevations, where conditions are often sketchier and more objectively hazardous. With more people recreating in a relatively small area, there’s a greater likelihood that people will be exposed to avalanches.

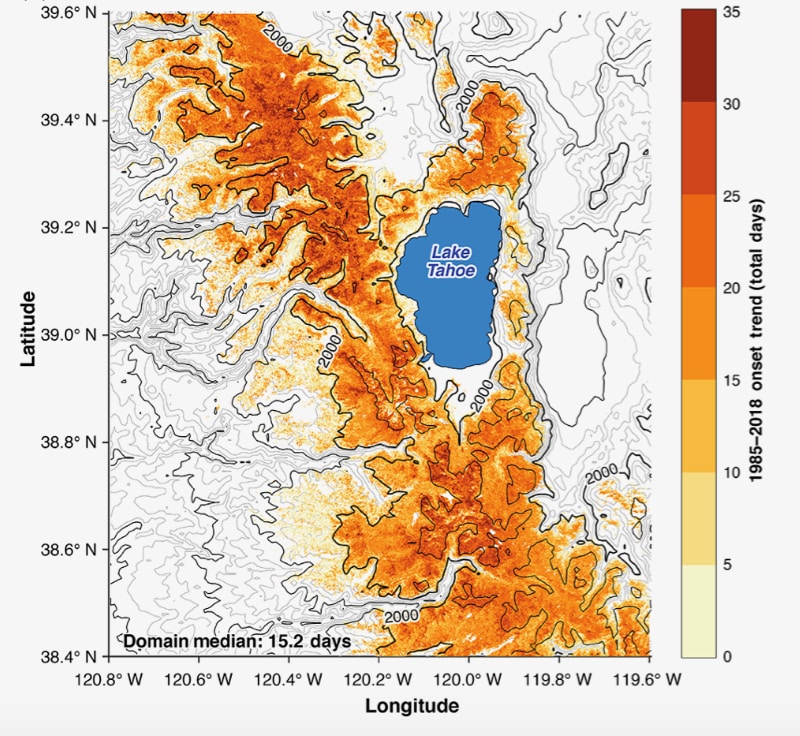

This graphic shows that snowpack accumulation is taking longer and longer–it’s now happening about 15 days later in the season than it did in 1985. Credit: Ben Hatchett.

DRI: What’s happening with our snowpack in the Sierra Nevada this year?

BH: This winter is a classic “what the heck?!” winter. It started off very dry, with well-below normal precipitation into November. Then we had a warm, wet storm around Thanksgiving to get us back to “normal” mid-winter conditions up high. Throughout December, the storms we got were cold enough to accumulate a healthy, above-average snowpack. January was very dry, but we had a few nice cold storms. This was followed by one of the driest Februaries on record. Basically, we enjoyed spring skiing conditions in February and early March that are more typical of April. Mid-March brought us an ideal snow-producing storm that did wonders for the ski conditions and made a nice dent in the snowpack deficit. So far, April has brought us another decent storm. These spring storms help to create interesting avalanche situations as the sun becomes increasingly intense and temperatures warm. While we’re still looking likely to end up with a below-average year, compared to the other recent drought years this season has far and away had the best ski conditions.

This winter, along with the other variable winters we’ve seen in the last decade, makes me wonder whether this is the jumping off point into a new kind of mountain recreation landscape, where we can go from excellent conditions to something that’s not so great in no time. I think the Sierra Nevada, and other maritime mountain ranges, are going to continue to become more susceptible to changes in weather and climate variability.

DRI: What drives you to continue doing this work?

BH: Just being in the mountains and trying to pick the optimal weather conditions for ski runs or mountain bike rides has been a huge motivation for my research. I’m most mentally productive when I’m climbing up mountains. You’re able to just let go of everything when you’re spending several hours going up a hill, whether that’s on skis, on a trail, on rock, wherever! It gives you a lot of time to think, observe, and consider.

I’m always trying to see new things and then better understand what I’ve seen. As a backcountry enthusiast, you get to see all kinds of interesting environments with different kinds of weather, geology, as well as human relationships to those places. Wanting to protect alpine environments and get other people psyched on them inspires my research quite a bit.