David Almanza, Ph.D., joined DRI this summer as a postdoctoral researcher in urban climate adaptation. He is working with Ariel Choinard in the Southern Nevada Heat Resilience Lab to examine how heat is impacting communities in and around Las Vegas. Born in Bogota, Colombia, Almanza grew up in Las Vegas and completed his Ph.D. at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, in 2023.

In the following interview, Almanza discusses his social science training, what it means to center research on your own community, and his love for Las Vegas eateries.

DRI: Tell us about your background and what brought you to DRI.

Almanza: Well, my academic background is in the social sciences. I studied the rhetoric of environmental policy for my Ph.D., and I was always interested in how communities were either included or excluded from decision-making processes through language. I was always curious about the sort of non-tangible elements in the world that shape everyone’s experiences, and I found language to be a way that I could explore that. And I think that connects with sort of my more creative side. I played multiple instruments growing up, and art was a big presence in my house.

I had an opportunity to work with Ariel Choinard last summer to help her create an overview of the organization around heat mitigation in Southern Nevada. This stemmed from my work at UNLV with the Public Communication Initiative. The goal of our work was to bridge the gap between scientists and the general public. We wrote materials to help simplify academic findings into messages that the public would find accessible, interesting, and engaging, and through that work, I met Ariel.

DRI: Did you want to be a researcher when you were a kid?

Almanza: Well, I wanted to be the president, and I wanted to be a reporter. I always had this sense that governance is important, but also that information is important. And I think in a way, that’s kind of what I do now, because I work with governing bodies on issues of public policy, and I work with communicating that to the public. In hindsight, I think I did want to be a researcher, I just didn’t have the language to put it into words.

DRI: Tell us about your PhD work at UNLV.

Almanza: I did a lot of archival work looking at the Paris Agreement, which is the international treaty that outlines efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change. I was always intrigued by the big picture, of how international policy will inform all these countries around the world. Being an immigrant myself, it gave me a way to examine what this looks like from an American standpoint, but also, what does this look like for a country like Colombia? I essentially was looking at which communities get a say in this international policy. Which industries, which experts? Who do we consider to be experts? Is indigenous knowledge and other citizen knowledge included? What concerns are being prioritized?

DRI: What is your role at the Southern Nevada Heat Resilience Lab? What will your day to day look like?

Almanza: The goal of my position is essentially to help Southern Nevada adapt to the changing climate as best as possible, and to research what climate adaptation looks like. On days where I’m not meeting with representatives and stakeholders, I’m researching how other countries respond to their climate needs. And that might look like examining how Medellin, Colombia has reduced their urban heat island effect, or how Athens is responding to their climate needs. Because my soil is people, and my lab is society, what I’m drawing from this is how the decision makers organize– what were the priorities? A lot of those things are transferable, or at the very least, we can learn from how those coalitions were formed to create the priorities that will be relevant to us.

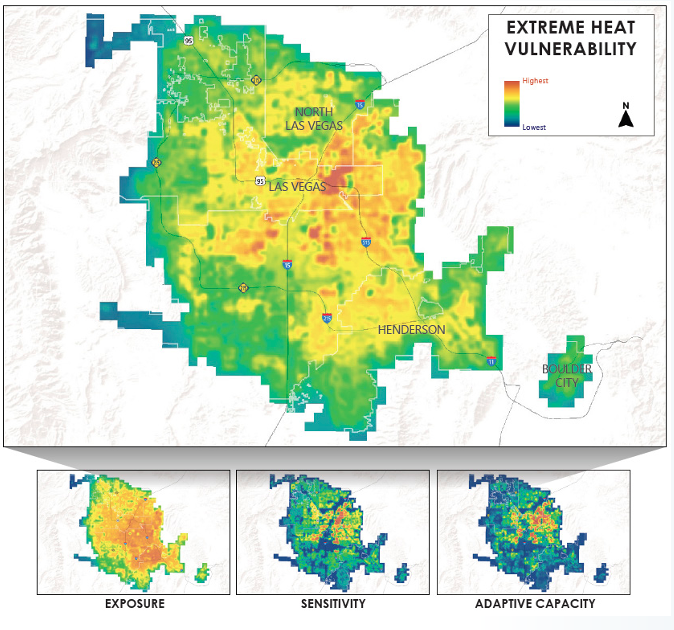

Because we are still setting the foundation for official heat mitigation work in Southern Nevada, my role has been to make sure that we have the information about heat that we need to inform the state’s policies and responses. For example, we are currently designing a Cooling Center study to hear directly from residents about their experiences. Something we have noticed when we look at the heat mapping that some of our fellow DRI scientists have conducted, is we see the human experience differs from the hottest temperatures to less burdened areas. Some people are faced with choosing between putting food on the table or paying their energy bills to keep their home at a safe and livable temperature. And so that human component is necessary for decision makers to be aware of, that heat is not just an inconvenience. Heat is not just something that is uncomfortable, it is deadly, and it has an impact on people’s physical and mental health. My everyday role is essentially collecting all of these different pockets of information and making them accessible so that when decision makers get in contact with us, we can supply them with the data they need to make holistic decisions that will benefit the community.

DRI: What are you most excited for in this new role?

Almanza: I think this is a crucial time, not just for climate change overall, but Nevada specifically, because we are creating our official response. This is an opportunity for us to rise to that moment and to be part of that team that can help create solutions for folks and have an impact on everyday people’s lives, and I don’t think you can put a price on that. As a researcher, to be able to see your work come to life in your community–that’s really exciting.

DRI: Why do you think it’s important to have research that focuses on issues facing local communities, like the Southern Nevada Heat Resilience Lab?

Almanza: Because we are the community, you and me. I know that sometimes when scientists and researchers say, ‘Oh, we’re studying the community,’ we tend to draw this imaginary line between the folks out there and us, the observers. But at the end of the day, we are the community. We walk out of our office and go to the grocery store with the community that we’re researching. Those are our neighbors, those are our family members, and we are the people that create and sustain these systems. In order for us to improve the world that we live in, we have to understand what is going on, what isn’t working, and how we can make it better.

DRI: What do you like to do when you’re not working?

Almanza: I’m a foodie. I’ll make a whole night out of it and just hang out with my friends trying the amazing food that we have here in Las Vegas. I will give a shout out to a place that I’ve been going to since I was in grad school called PublicUs. Excellent coffee, great people.

DRI: Is there anything else that you want the DRI community to know about you?

Almanza: As a qualitative scientist, I would say that it’s okay to celebrate your point of view. This means to acknowledge our standpoint and our background and experiences. For myself, being an immigrant and person of color, that informs how I perceive the world. And I think when scientists acknowledge those things, we can use that to empower ourselves. It’s not necessarily a flaw in the scientific approach, but it actually gives us deeper insights into pockets of our own experiences that other people can relate to. Qualitative science has the power to say that your bias may be your insight into a question that hasn’t been asked yet. So even for my colleagues who are physical scientists and are working to avoid those biases, I would encourage them to embrace those moments where their own identity can inform what kind of questions could be asked. I think that allows all of us to celebrate our identities, as well as what I think is at the heart of science, which is curiosity and wonder.