Rachel Kozloski is in the second year of her Ph.D. at the University of Nevada, Reno. Under the mentorship of DRI’s Monica Arienzo, Kozloski focuses on the movement and characteristics of microplastics in ground and surface water. She recently received the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Award (GRFP), a prestigious grant awarded to students pursuing research-based graduate degrees in the natural, social, and engineering sciences across the US.

Last year, Kozloski worked with researchers in Cambodia, studying the impact of plastic pollution on the water quality of the Mekong and Tonle Sap Rivers. As part of the microplastics lab at DRI, her research interests also include microplastic movement between surface and groundwater resources in the Reno/Tahoe area.

Microplastics are everywhere and are of growing interest to hydrologists studying the health of aquatic ecosystems and the environment. In this interview, Kozloski breaks down the ubiquitousness of microplastics and their impact on our local water systems in Northern Nevada. This interview was lightly edited for length and clarity.

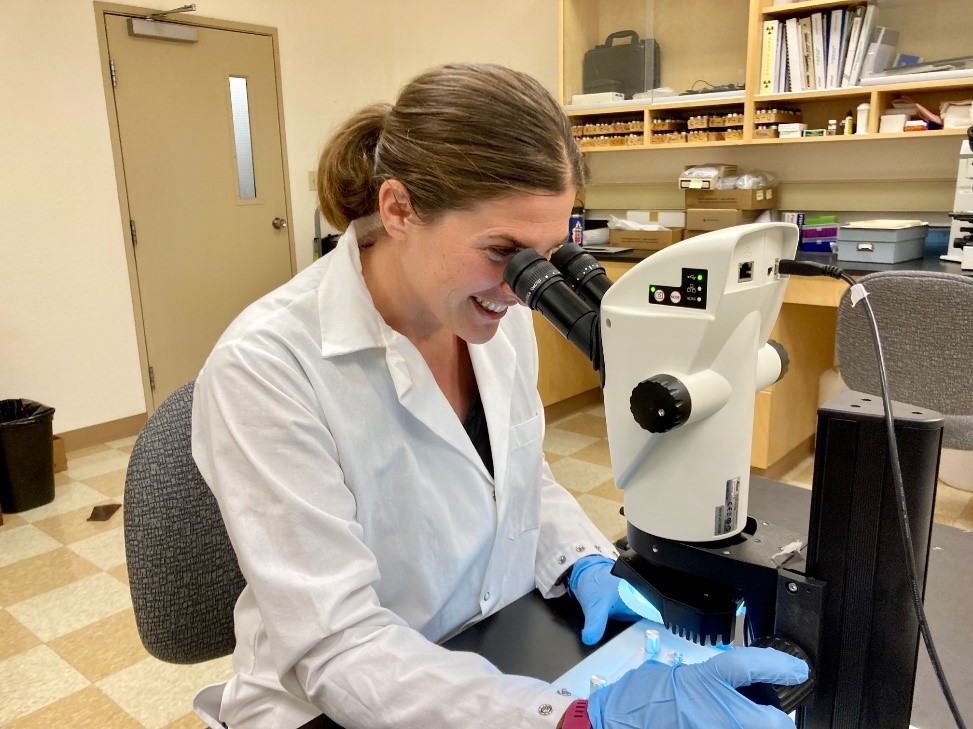

Above: DRI Graduate Research Assistant of Hydrologic Sciences, Rachel Kozloski.

Credit: Jessi LeMay/DRI.

DRI: What was the journey like getting to this point and what inspired you to pursue your research?

Kozloski: After three years of undergrad studying aviation, I took a break from school. When I went back to finish my degree, I ended up studying soils and agricultural ecology, which was a big shift. By the time I’d finished I’d spent six years in undergrad. I was tired, and I was just really overwhelmed by the debt. All I could think about was getting out and getting to work. All my professors pushed me to consider grad school, but I needed money. So, I went immediately to work. I worked in Carson City for a little consulting firm there. It was a huge learning experience. But within the first three years, I realized that to do the work I really wanted to do, I needed to go back to grad school. But I didn’t know how to do it, because I had young kids and life just kind of needed to happen. I stayed in consulting and got my family to a point where it was stable. It took me about 16 years of working before my kids were old enough that they didn’t need me so intensely and I had enough savings.

When I started to look for grad school opportunities, I was hearing more and more about microplastics and artificial groundwater recharge. I was a big fan of DRI, and then I saw that Monica Arienzo was looking for a grad student. I just happened to come across it at the right time, and it was what I was looking for. I was really excited. My second semester in grad school I had this opportunity to go to Cambodia for two weeks and collect all kinds of samples and just be in a totally different environment and think about water development in a different way. I’ve been able to work with some neat folks; Cambodian researchers and researchers from all over the world who are working on these projects. It was a huge opportunity.

DRI: What are you currently working on? And what questions and challenges are you trying to address with your research?

Kozloski: I’m really interested in how waste management practices and land use patterns affect microplastic concentrations in water systems. I’m also transitioning to my groundwater and surface water connectivity work, which is what I wrote my GRFP proposal on. I’m getting ready to start collecting samples this summer.

Microplastics are a novel pollutant. We’ve been making plastic for more than 70 years, but we’ve only started to consider the consequences of that in the last couple of decades. We don’t have a handle on how microplastics move, how they’re formed, what their relationships are with other hydrologic variables like bacteria, biofilm, mercury, and other pollutants.

My focus is looking at how human activity affects the amount of plastic that’s in our water. And then how do microplastics move between surface and groundwater systems and soils? These tiny particles carry all the chemical signatures of what they were manufactured with, including all the additives and chemicals that have gone into them. We know they’re found in surface water and groundwater. So, then the question is, how are they moving? How fast are they moving? How deep do they go? Under what situations are they moving between surface and groundwater systems? If we do find movement, that can help in designing systems that can protect our groundwater, especially when we’re talking about climate change and needing to be really careful about our resources.

Rachel in the microplastics lab at DRI.

Credit: Monica Arienzo/DRI

DRI: What are some characteristics of microplastics that you’ve analyzed, and how do you identify true microplastics?

Kozloski: Microplastics can range in size from as big as a pencil eraser all the way down to smaller than a bacterium. Those tiny particles that are less than a millimeter down to the micrometer scale, those are the ones that I’m really interested in. We use a machine here at our microplastics lab, the micro Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). It shoots a light at the particles, and then every particle has a spectral signature of what it absorbs, and what it reflects.

There are spectral libraries of all kinds of materials: natural materials, manmade materials, all kinds of chemicals. So, over the last decade or so, people have been working on developing a plastics library of spectra signature. It’s not complete, and it’s not always perfect, but for a lot of the particles we’re able to see their spectral signature and then match that signature against libraries of known materials. It can be really hard to identify microplastics visually because especially in really organic, active environments, everything gets covered in mud and a film of biological growth. But using the FTIR we are usually able to identify them.

DRI: What other challenges do you come across in the lab and while doing your fieldwork?

Koslozski: The methods aren’t set in stone yet. Everyone’s constantly trying to come up with a better and different way to do things. But that means it can be hard to compare results between studies. Some particles are so small that our instruments can’t detect them. Right now, we can only look at particles down to about 20 microns. Being able to see even smaller particles would be amazing, because we know the smallest particles are the most ubiquitous. If you took a sample of water from a site, and you broke it up just by size categories, as you get smaller, you’d find more and more. One of the biggest problems is the sheer volume of particles in this small size category, because they’re really difficult to measure and really difficult to identify. But they’re also important.

Another big challenge is getting the microplastics out of the material we found them in and separating them from the soil and clay particles. It’s just a time consuming and labor-intensive process. Our environment is full of plastic. It’s everywhere: from our clothing to our offices and the air, so we have to be careful about contamination in the lab as well and make sure that our samples are protected.

Above: Rachel takes water samples from the Mekong River in Cambodia.

Credit: Monica Arienzo

DRI: In what ways are microplastics hazardous to water systems and the environment?

Kozloski: There have been studies that have shown that microplastics can have an impact on critters that are eating them, blocking digestive tracts and things like that. Filter feeders can accumulate them, and they may be able to transfer up the food chain. But a lot of studies that look at the environmental effects, or the effects on organisms, are using higher concentrations of microplastics than we currently see in the environment. So, it’s hard to take that back and correlate it directly with the amount of plastics that we’re seeing right now in the environment. We do know that microplastics can act as vectors for different chemicals. But as far as the toxicity of the plastics themselves, we’re still finding out.

I think the thing to keep in mind is that we have produced a lot of plastic, and we’re producing more every year. We recycle only about 9% of plastics. The rest go to landfills or get lost in the ocean. And so, everything other than that 9%, every bit of plastic that’s been made in the last seventy years, is still out there in a landfill, or blowing around in the wind, or getting lost in water, and all of that will break down over time into microplastics. The amount of microplastics that we see in the environment right now is only going to keep increasing until we get a handle on the situation.

Above: Rachel sorts out plastics from a fisher’s catch in Cambodia.

Credit: Monica Arienzo

DRI: Why is researching microplastic movement and contamination in water systems important in the face of extreme and unpredictable precipitation events, population growth, and climate change?

Kozloski: I think it really comes down to managing the resources that we have, especially considering population growth and climate change. As I said before, we’re seeing more and more plastic produced, and much of that plastic is not managed well and is released into the environment. So, understanding the consequences of our decisions is important, especially when it comes to resources becoming more limited. Groundwater seems like a protected resource since it’s down in the ground. But really understanding how and where there can be movement of those particles between surface and groundwater systems so that we can understand how to protect our groundwater better is important. Also, understanding how microplastics are moving into our surface water systems, including the Truckee River and our terminal lakes in Nevada. Once it goes in there, it’s not coming out. So, we need to be really careful about what’s being released and how we manage it.

Above: Collecting microplastics samples on the Mekong River, Cambodia.

Credit: Monica Arienzo/DRI.

DRI: How will receiving the Fellowship Award impact your work and career, and what research lies ahead?

Kozloski: For me, it’s like living the dream. I’ve wanted to be in research so badly. I love being able to ask hard questions and then just work to find solutions. I have a really curious mind. I think if you talk to any grad student, they will tell you that financially, it’s really tough. Reno is growing like crazy, everything is expensive, and schools really have not been keeping up with the cost of living. This award is life-changing for me and allows me to take care of my family and to continue my work. Before receiving the award, I had been considering whether I needed to take a couple of semesters off and work to rebuild my savings and be able to take care of my obligations as a parent while also pursuing my dream for research. So, for me, this is a huge relief, because it gives me financial security knowing that I’ll be able to continue my program and take care of my family with a lot less stress. At the same time, I recognize that it would be great if everyone could have that kind of security.

DRI: What advice do you have for students who want to pursue graduate school, particularly in hydrology?

I would say if you’re one of those people who is full of questions and loves digging deeply into things, go for it. I feel fortunate to have a great group of people that I work with, an advisor that’s been able to give me these crazy opportunities, and the chance to pursue something that was just taking up space in my brain rent free. For other students out there, there are amazing researchers who are looking for folks to work with them and partner with them on these great questions. And if you are curious minded and want it, go for it. It can be hard in grad school trying to figure out how you’re going to make ends meet, but there are resources available. There are lots of scholarship opportunities. And opportunities to TA and work and fellowships. There are ways to make it happen. You’re not alone in this. You can make it work, and there’s great support to get to where you want to be.

For more information about the microplastics lab at DRI, visit: https://www.dri.edu/labs/microplastics/