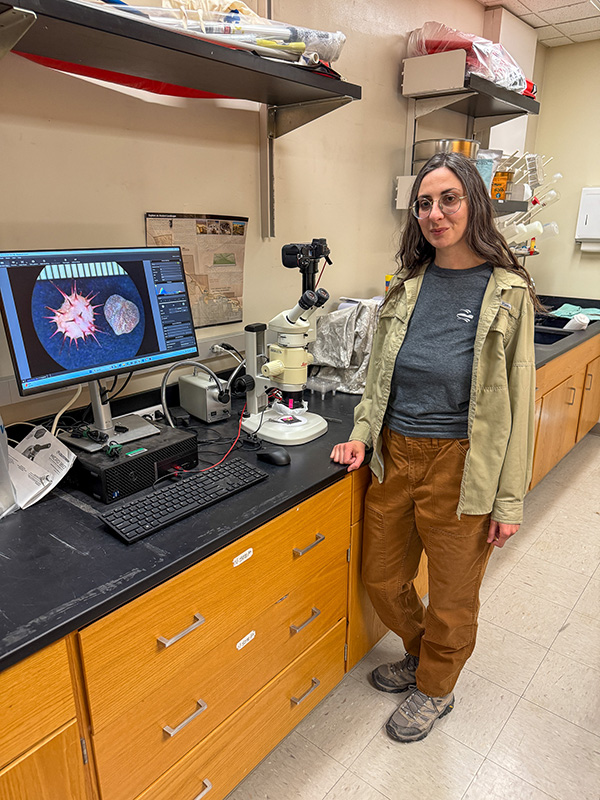

The ecologist and illustrator created a first-of-its-kind seedling guide to help land managers and community members identify native plant seeds and aid with restoration work.

Nevada’s desert landscape is filled with life that is hidden to human eyes. But when conditions are just right, typically following a particularly wet winter, billions of seeds burst to life in vibrant, colorful displays of blooms that can even be seen from space. When these wildflowers inevitably dry out in the desert sun, they’ve replenished the soils with the seeds of future blooms. Some of these seeds will remain there for decades, waiting for the right set of conditions that will allow the plant to flourish. In fact, scientists have successfully sprouted desert seeds found to be 2,000 years old.

DRI’s Tiffany Pereira specializes in the desert plants of the Las Vegas region, particularly the Las Vegas bear poppy. With silver-tinged furry leaves that grow in a rosette and occasional bright yellow flowers topping slender stalks, the plant is a charismatic example of the hardiness of species adapted to the harsh Mojave Desert environment. While working on her master’s degree at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Pereira wanted to illuminate every aspect of the species’ life cycle, including the invisible seeds scattered throughout the soil. To do this, she needed to collect and sift through a lot of dry desert soil, and quickly realized that there was no good guidance available that could help her identify the seeds she was finding. So she decided she’d fill that gap in scientific knowledge by producing one herself.

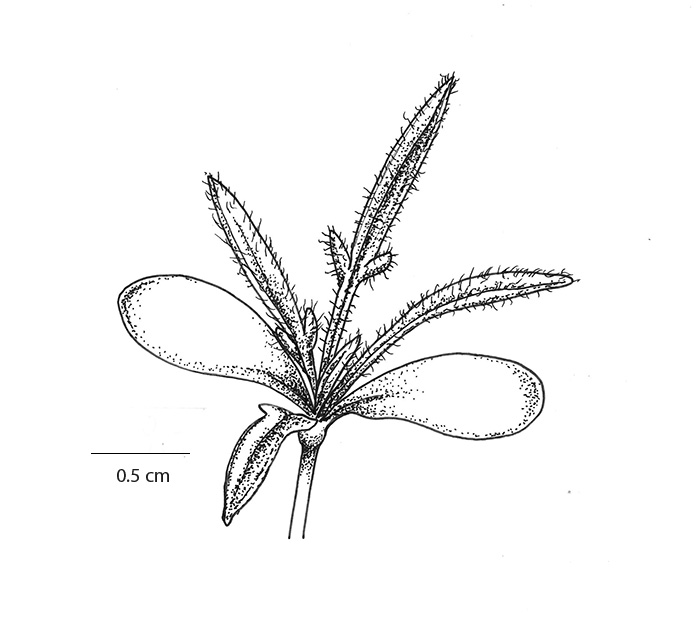

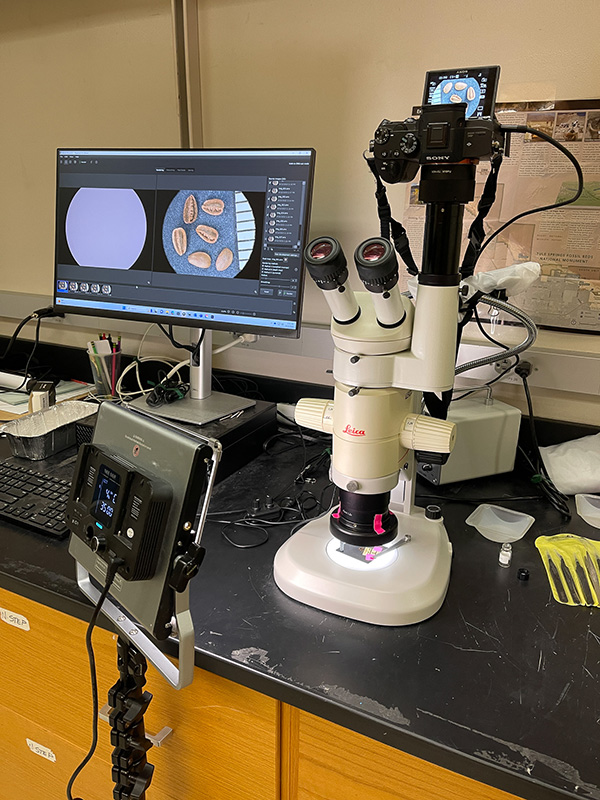

As an artist and a scientist, Pereira is familiar with the long tradition of scientific illustration, or the practice of using art to create meticulously detailed drawings of plants and animals. By utilizing her artistic skills, she realized she could produce a guide of Mojave plant seeds and seedlings that could be used by other scientists, conservation workers, and landowners for generations. The guide includes photos of mature plants, microscope photos of seeds, and hand-drawn illustrations of seedlings for 86 species native to the deserts of Las Vegas.

“Now more than ever, we need to find a way to bring scientific discourse to the public using a relatable medium,” Pereira writes in the guide’s foreword. “As the adage says, a picture is worth a thousand words.”

DRI sat down with Pereira for more information about her goals and inspiration for the project, the benefits of fusing art with science, and the miracles contained in the tiniest seeds. Following the interview is Pereira’s foreword for the Seedling Guide.

In the words of the author Ray Bradbury, “Science is no more than an investigation of a miracle we can never explain, and art is an interpretation of that miracle.”

View the Mojave Desert Seedling Guide

DRI: What inspired this project?

Pereira: It started around 2018, during my master’s degree at UNLV. I was working on a conservation project looking at the change in soil seed banks for the Las Vegas bear poppy over time. I started sieving through soil to see what seeds I could pull out and collecting soil samples from the field to see what grew from them. As I was doing this, I found it very difficult because we would pull seeds and have no idea what they were. In some cases, we didn’t even know if something was a seed. And there were very few resources for us to check to see what seeds these could possibly be. We also had to grow the seedlings to a certain point before we could positively ID them. I started keeping track of those little baby seedlings as they were coming up in the greenhouse. And I thought, why not just keep track of them and create a guide so that other people doing this research can have an easier time than I’m having?

When I presented about this project at a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) conservation conference, someone from their office reached out and let me know that they had a funding opportunity that could support the work. That was my first formal grant to combine my love of both science and art and continue that work that was started in my master’s– but really started as a kid who loved both.

DRI: How did you decide to include illustrations?

Pereira: Well, I am both a scientific illustrator and an ecologist. I find that quite a few people in the botany field end up being illustrators as well, because scientific illustration is an old form of artwork used to share scientific information. It was borne from a time when there were no computers or fancy graphics software to document findings, and botanists actually still frequently use botanical illustrations to identify plants. If you look at most flora guidebooks, they still have hand drawn or digitally drawn illustrations. I wanted to keep that spirit alive and just do something a little bit different with the seedlings, because it’s a part of the plant that isn’t typically focused upon but that people working on restoration projects still need to identify. So, it’ll help people out to see their little cotyledons and embryonic leaves.

DRI: Tell us about your process for identifying each stage of the plant.

Pereira: Well, a lot of people like me who work on seed germination ecology look at determining what a seed from a specific species needs to germinate. So, what’s the temperature requirement, what’s the water requirement? Is there a cold stratification or heat stratification? All these different combinations of things can result in different species needing different things at different times. So, it gets kind of complicated, and as a result, we can have these gorgeous displays of wildflower blooms in the field – or not, like this year, where we really haven’t had much rain so there’s really nothing coming up around Las Vegas.

The seedlings are a very vulnerable stage for plants– anything can eat them, or if those conditions aren’t right, they may not continue to grow anymore. And for landowners, it’s important to know what’s coming up naturally in the seed bank of their property. But it’s also important for land managers to know what’s coming up on the lands they manage so that they can augment that seed bank if they’re working on restoration projects.

DRI: How long do most Mojave seeds lie dormant in the soil seed bank before germinating?

Pereira: Well, all species are different. Some have an annual seed bank, and those typically turn over on a yearly basis. However, even within those not all the seeds germinate each time. What’s great about that is that it’s a form of bet hedging where the plant doesn’t throw all its resources out at the same time. Because you might have a year where it starts off great, and then it gets really hot, and everything dies before there’s flowering and reseeding. Some species have persistent soil seed banks, where the seeds just turn over constantly, but it could be 10 or 15 years before there’s a good bloom between them. I study a species called the three-corner milk vetch that had a great year last year, but the prior three years weren’t that great. Without those soil seed banks, our Mojave species simply would not exist, and all the animals that are dependent on those botanical resources would also have a hard time. For example, desert tortoises don’t have a great banquet out there for them in this area, unfortunately, but they can hold on to reserves even from last year.

DRI: In your recent field work, have you seen many native Mojave plants germinating in the deserts around Las Vegas?

Pereira: Unfortunately, we’ve had quite a bit of a drought year, with 217 days without measurable rainfall in Las Vegas. That definitely impacts our plants. We are seeing some of the perennial plant species like the larger shrubs responding to the decent rain we had in February, but there are very few wildflowers coming up.

DRI: What do you want people to understand about desert plants?

Pereira: I just want them to appreciate all aspects of the lifecycle. Our guide showcases these small seeds, some of them just a millimeter in diameter, and these small packages hold the genetics and the ability to create a whole new life sprouting from the earth. Something so small can become something so big. When we look out at the landscape, it’s easy to lose sight of the interdependence of everything, from rainfall and temperature to the timing of those things. But everything really is connected, from a tiny seed to a little seedling to the Joshua trees, aspen trees and cottonwood trees that you see.

DRI: How does your art inform your work as a scientist and vice versa?

Pereira: Science takes a lot of creativity, whether that’s a traditional art form like drawing with pen and paper, or something more graphical, or even just designing an experiment — it is a creative process where you must think outside the box. It just might not be creativity in the narrow realm that we tend to think of it as, and so I think a lot of scientists such as myself can think about things in a creative way, and that only serves to make us stronger and better scientists.

DRI: Is there anything else that you want to share about this project?

Pereira: My gratitude for my DRI colleague Tsvetelina Stefanova and Judy Perkins from BLM, who both helped bring this project to life. And Matt Berger too, who provided the pictures of the mature plants that we included in the guide. I’m just so thankful to everyone who helped make it happen.

Foreword to the Seedling Guide

In today’s world of constant contact, scientists face a mounting problem—how to effectively communicate. Jargon, information access, and apathy are a few of the hurdles scientists face while engaging the public. How can we present data in a way that engages and impacts an audience, especially hard-to-reach individuals? As a solution to this conundrum, science and art should not exist on separate planes, polarized by different processes. Creative media can powerfully convey scientific knowledge. By harnessing one of the oldest and most ubiquitous languages of civilization, scientists can bridge gaps, convey complexities, and build trust.

Scientific illustration is the accurate depiction of objects and concepts in the sciences, including wildlife, botanical, and medical illustrations, but also textbook illustrations and sculptures. While these creations can be beautiful works of art in and of themselves, the focus remains on accuracy, reflecting the findings of science and technology, and taking the viewer to the often unobservable.

The earliest scientists did not have computers or cameras to document their work. Instead, they relied on writing and artwork to report their findings and collaborate with colleagues in their fields. This golden age of scientific illustration propelled advances in the sciences. Some of the most important discoveries in science and medicine are preserved through hand-rendered illustrations. Leonardo da Vinci, Charles Darwin, and John James Audubon are just three examples of the numerous researchers of centuries past that were both scientists and artists. In their footsteps, many of today’s scientific illustrators are also trained in both art and science, providing a necessary and often underutilized service to fellow researchers who wish to visualize their work.

Traditional approaches and techniques of scientific illustration include careful renderings in pen and ink, to precise painting in watercolor and oil paint. The advent of printing brought woodcuts, copper etchings and lithography, which in most cases, outside of a fine arts realm, have given way to full-digital printing and even digitally rendered drawings. Scientific illustration, and more specifically, botanical illustration, has evolved with technological change. A combination of practices is often used today, with hand-drawn or painted images digitally processed for reproduction and print. The use of photography, however, as a technique for scientific illustration has been met with criticism in the past. Despite this, some of the earliest photography techniques were used to create unique specimen guides. Anna Atkins’ 1943 work, British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (cyanotype blueprint process invented by Sir John Herschel), is an extraordinary example of the first scientific manual to be printed using photography. Today, many modern field guides use a combination of photography and drawing. Embracing digital techniques may come slowly in the world of botanical illustration. However, new advances in photography techniques and software can be combined with traditional techniques to create highly detailed images fit for sharing with the scientific community and public in the modern digital age.

With this concept in mind, the goal of this project was to develop a novel illustrated guide for identifying Mojave native and exotic plant seeds and germinating seedlings.

We worked with the Bureau of Land Management to identify priority restoration species. The focus on young seedlings (cotyledons and first leaves) is one of the first of its kind to assist in soil seed bank analysis, restoration projects, and identifying natural regeneration in the field. The ability to identify native plant seedlings and assist their establishment is valuable. Agency land managers could use this guide for assisted natural regeneration at restoration sites. There are private landowners interested in using native plants for landscaping but have trouble locating native plants for sale.

Additionally, seed descriptions are often hard to interpret, and images or illustrations are nonexistent for many species. We hope the artwork of this unique project will provide a valuable tool for land managers, fellow researchers and for public education to reach a wider audience.

Now more than ever, we need to find a way to bring scientific discourse to the public using a relatable medium. As the adage says, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Tiffany Pereira

Associate Research Scientist, Ecologist

Pereira Conservation Ecology Lab

DRI