DRI scientists conduct a wide range of research on wildfire related topics to help policymakers, fire managers, and community members navigate challenges to public safety and health.

Southern California has seen some of the most destructive wildfires in the state’s recorded history in recent weeks, with the Los Angeles communities of Altadena and Pacific Palisades experiencing unprecedented loss. While fire has always been a feature of California’s landscape, the size and intensity of blazes is known to be increasing due to a number of climatic and societal factors. DRI scientists conduct a wide range of research that explores nearly every aspect of wildfire management and prevention, from detailed examinations of drought conditions that fuel the infernos, to working with communities to help them understand the risks of wildfire smoke. Our researchers work together to produce research that crosses scientific disciplines, fostering an approach that strives to overcome traditional academic silos to produce actionable information and solutions for communities.

In light of our broad range of scientific expertise on the subject and in recognition of the need for innovation, DRI held our inaugural global initiative intended to foster an Adaptable World Environment (AWE+) last summer in Las Vegas, an event that brought together scientists, policymakers, first responders, and industry leaders for two days to cultivate resiliency. Titled “Wildfire Recovery and Resilience: Working Across Silos to Drive Solutions,” the initiative brought hundreds of people together from across the country to build connections across communities and specialties while helping leaders envision a future of manageable wildfire.

“In 2023, our DRI Foundation trustees recognized that fortifying communities against a shifting climate requires more than just science; it requires the collective resolve of communities and stakeholders to come together to advance resiliency and adaptability,” said Kumud Acharya, President of DRI. “From this belief, AWE+ was born. It provided a unique opportunity to identify and address areas of need in their respective communities.”

In the following Q&A, a selection of our scientists answer some of the most pressing questions about the environmental conditions that lead to the most devastating blazes and offer previews into some of their most relevant research.

How has wildfire risk changed in recent decades, and what made the recent fires in southern California so explosive?

Answered by Tim Brown, Research Professor of Climatology and Director of the Western Regional Climate Center

Highlighted research:

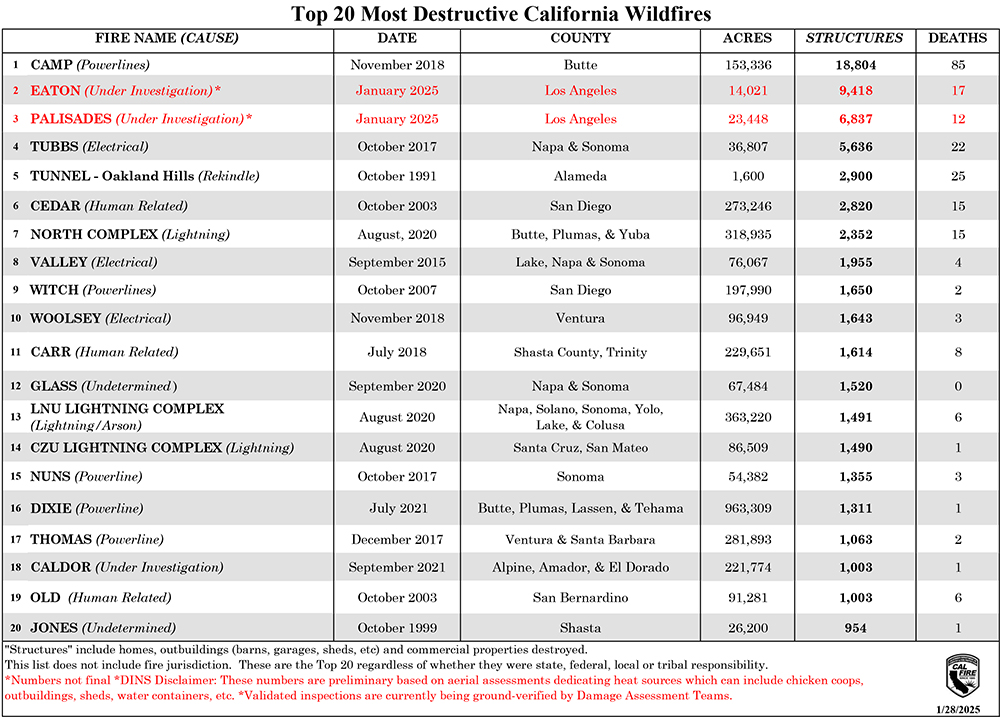

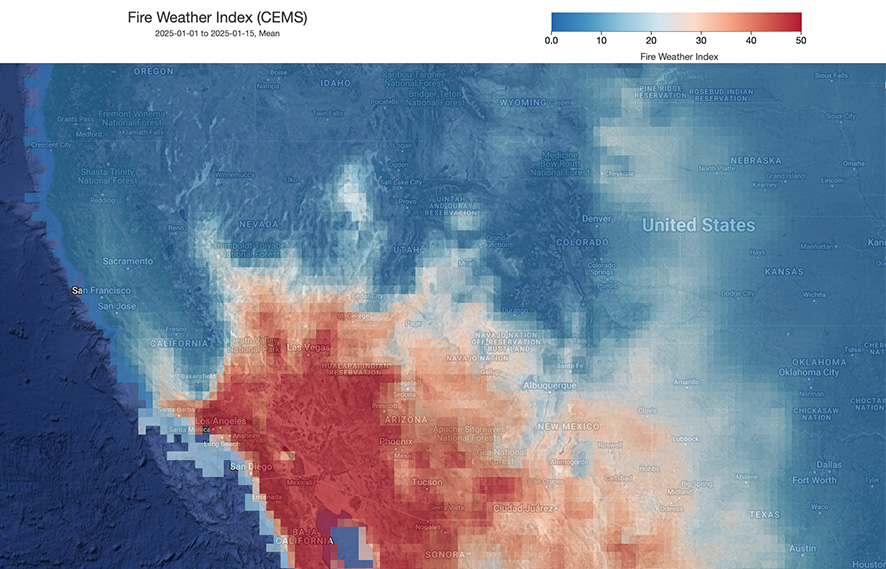

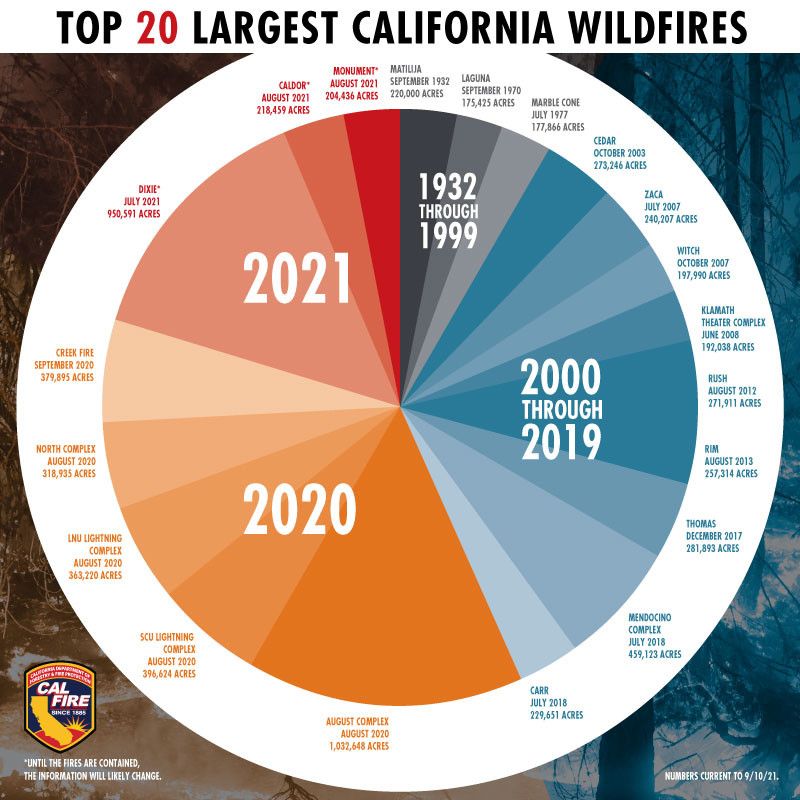

“Large fires are driven by hot, dry, and windy weather and topography when sufficient vegetation fuels are available to ignite and burn. Destructive fires are the confluence of climate, people, fuels (and topography), and buildings and structures can become part of the fire — and in extreme cases, an urban conflagration. The potential for fire is being exacerbated by the warming trend in the past three decades that enhances drought. Dry weather dries the vegetation. But fire potential also results from wet periods (such as the winters of 2022-23 and 2023-24) providing plentiful moisture for vegetation fuels to flourish in the spring.

The Palisades and Eaton fires were driven by extremely strong Santa Ana winds that makes firefighting very difficult. Depending on the location, these winds were near record speeds due to a high-pressure system to the northwest off of the coast and a low-pressure system to the southeast. The mountainous topography can accelerate this ‘packed’ wind downhill. The vegetation fuels were dense from the very wet previous two winters and precipitation from the remnants of Hurricane Hillary combined with the fact that there was substantial fuels accumulation from not burning in at least 45 years. It is important to note that overall, this is a fire prone region – there have been fires for millennia in southern California. The dry fuels were dense and plentiful amongst the homes in the Palisades and Eaton fire areas. Most of these homes were ignited either by embers or radiant heat from the house next door. The vegetation was very dry due to the lack of precipitation for several months. Winter rains typically begin in November and extend through the winter, but for this winter up through January precipitation was at near record dry. This and a warm atmosphere combined to dry the fuels to critical flammability levels. This level of fuel dryness is commonly seen in August and September before the rains come, but not commonly in January. To summarize the event, severe wildfire potential was generated from very dry and continuous fuels combined with very strong winds. This led to extreme wildfire conditions with high intensity and rapidly spreading fire where control was not possible, thus overwhelming suppression resources. Nearly all of the structures involved were ignitable and vulnerable. The unfortunate outcome was a fire disaster – an urban conflagration with multiple structures burning at once, that was not controllable and overwhelmed suppression efforts forcing crews to initially focus on evacuations and life safety.”

How do atmospheric river storms — and conversely, an increasingly dry climate — contribute to wildfire risk?

Answered by Christine Albano, Associate Research Professor of Ecohydrology

Highlighted research:

- Increasing Hydroclimatic Whiplash Can Amplify Wildfire Risk in a Warming Climate

- A Multidataset Assessment of Climatic Drivers and Uncertainties of Recent Trends in Evaporative Demand across the Continental United States

“We typically associate atmospheric rivers with winter flooding, but they can be an important precursor to fire activity in drier regions. Storms resulting from atmospheric rivers promote plant growth that wouldn’t otherwise occur, and those plants fuel fire growth once they dry out. A warmer atmosphere can hold more water, which can both intensify atmospheric river storms when they occur, and cause more rapid drying of plants as it pulls more water from the land surface, extending the amount of time they are flammable. The southern California wildfires are a frightening demonstration of how this see-saw effect can contribute to wildfire risk.”

What are some of the biggest challenges with translating scientific research on wildfire risk into actionable changes?

Answered by Tamara Wall, Research Professor of Atmospheric Science and one of the lead researchers for the California-Nevada Adaptation Program

Highlighted research:

“We understand a lot about why structures burn in the United States. Our challenge is really addressing the gap between what our research and our evidence from the field tells us and what is happening with implementation. We have lots of research and field evidence that shows that keeping a five-foot non-flammable perimeter around your home is a great, and relatively inexpensive, way to reduce the risk of structure damage. But despite the evidence, a lot of people resist making this change. My Ph.D. research focused on place identity, and I’ve been thinking a lot about how when we’re asking people to change what their homes and neighborhoods look like, in some ways, we are asking them to change how they conceptualize themselves, and it’s a bigger ask. A five-foot perimeter doesn’t sound like a lot, but you are asking people to change their environment, and their whole community could look different. It could mean replacing wood fences with metal ones, and a lot of people resist these changes. I think we need to find a way to articulate these tradeoffs in a way that understands the emotional component. Because these are emotional decisions, and we’re often treating them like entirely rational decisions.”

What is the most important thing to understand about how drought conditions impact wildfire risk and how this trend might be changing over time? How is your current research advancing knowledge in this area?

Answered by Dan McEvoy, Associate Research Professor of Climatology with the Western Regional Climate Center.

Highlighted research:

“Prolonged droughts are one of the primary causes of excessively dry fuel moisture (dead and live vegetation) that leads high fire danger. In a warmer climate, like we have seen in the 21st century, high temperature and extreme heat waves act to further dry out vegetation and soil moisture, and the drying happens more rapidly than in a cooler climate. My research has been working towards developing relevant indicators and tools for monitoring drought conditions as they relate to wildfire danger and informing those in the wildfire management and forecasting sectors.”

How is Nevada working to improve our drought monitoring network and early warning systems, and how might this inform wildfire planning and response?

Answered by Dave Simeral, Associate Research Scientist of Climatology and one of the national authors of the U.S. Drought Monitor

Highlighted research:

“Nevada is both the driest state in the U.S. and one of the places most frequently impacted by drought. In the past 25 years, Nevada has experienced four distinct multi-year drought episodes, which have significantly impacted the state’s natural resources (e.g., forests, wildlife) as well as a variety of sectors including agricultural, economic, public health, and water resources. In response to the challenges Nevada has faced during the recent drought episodes, faculty from DRI’s Western Regional Climate Center have engaged in numerous drought-related applied research projects with federal and state-level partners including NOAA’s National Integrated Drought Information System (NOAA NIDIS).”

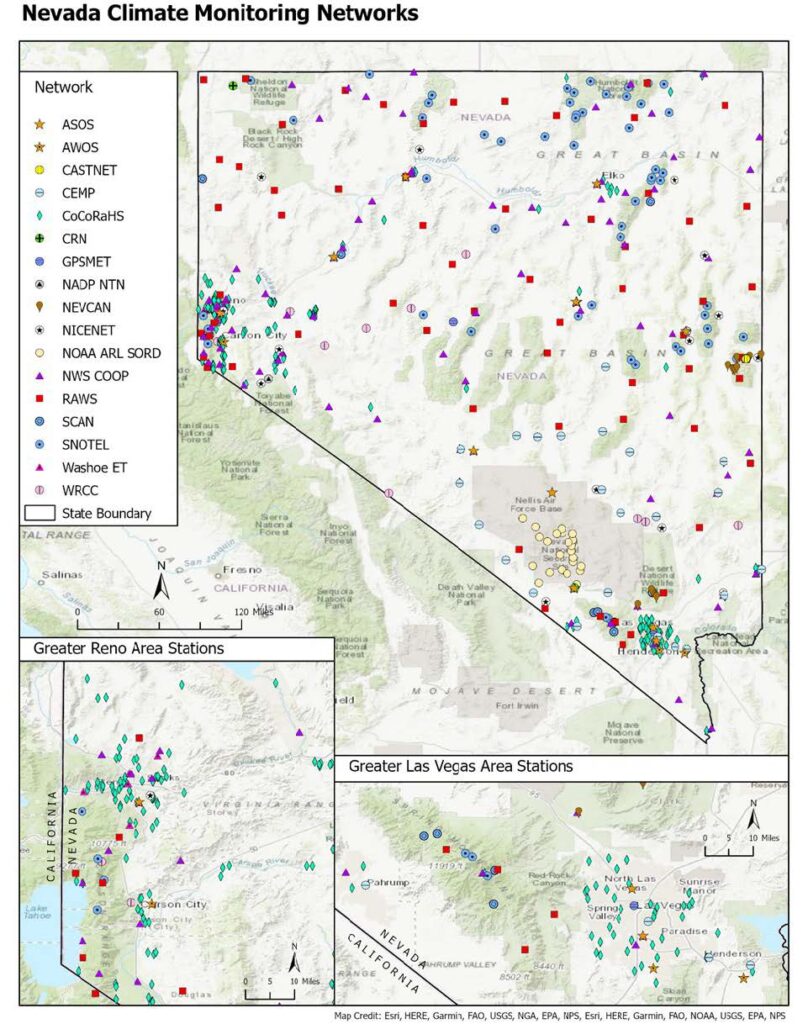

“One recent project, in collaboration with the Nevada State Climate Office, ‘Evaluating Nevada’s Drought Monitoring Network to Improve Drought Early Warning and Response,’ set out to assess the state’s drought monitoring capabilities, identify major monitoring gaps, and make recommendations on new monitoring site locations—a recommendation coming out of Governor Sandoval’s 2015 Nevada Drought Forum. The project was completed in 2023 and one of its outcomes was completion of a comprehensive report summarizing the findings and providing recommendations that would serve as a guide on how to improve the state’s drought monitoring capabilities that provide critical data to decision-makers, stakeholders, and the general public. Moreover, the project made recommendations related to specific under-served parts of the state in terms of not only gap identification, but needs for more comprehensive instrumentation that have the capability to not only measure rainfall, but snowfall accumulations through the cool season. These enhancements would help better inform a variety of decisions including weekly input to the U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM) by the NOAA NIDIS California-Nevada drought early warning system team, which provides input to the USDM. The weekly USDM map represents a real-time ‘snapshot’ of drought conditions nationally and serves as the primary data source for eligibility for a variety of federal drought disaster relief programs that are critical to Nevada’s farming and ranching communities. Moreover, improved monitoring capacity also serves to better inform response plans developed by resource managers that make critical decisions related to wildland fire activity, wildlife management, and water resource planning efforts.”

How can community members protect their health during wildfire smoke events?

Answered by Kristin VanderMolen, Assistant Research Professor of Atmospheric Science, and Yeongkwon Son, Associate Research Professor of Environmental Health

Highlighted research:

“There are several ways that community members can protect their health during wildfire smoke events. A good place to start is by checking local air quality for guidance on potential health risks. The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) AirNow Fire and Smoke map shows air quality, fire locations, and smoke plumes. The Nevada Division of Environmental Protection’s (NDEP) and DRI’s “rural NV smoke” website (https://ruralnvsmoke.ndep.nv.gov) provides air quality information for Storey, Pershing, and Elko counties. While the potential health risks may be greater for some people – like older adults, pregnant people, children, individuals with heart, lung, and certain other chronic conditions, and outdoor workers – it is important for everyone to protect themselves. The best way for people to do that is to leave areas where wildfire smoke is present, but this is often not an option because of the need to fulfill personal responsibilities, lack of mobility or resources, and pervasiveness of wildfire smoke. When leaving the area is not possible, there are more options for protection indoors than outdoors. To keep indoor air clean, it is recommended that people consider closing windows and doors, turning off window AC units/fans and evaporative (or swamp) coolers that lack particulate filters, turning on portable indoor air cleaners, and if they have it, running HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) on recirculate mode with the fresh air intake closed. When possible, MERV 13 or HEPA filters should be used in filtering devices as these are designed to capture very fine particulate matter that can enter deep into the lungs. Then, when outdoor air quality is good, ventilate indoor air to remove pollutants that may have accumulated during the wildfire smoke event. To reduce exposure to wildfire smoke outdoors, it is recommended that people consider avoiding or reducing physical activity and taking more breaks, and if it is very smoky or if a person is more at-risk, wearing an N95, KN95, or NIOSH mask or respirator. Each person will have different options available to them given their type of employment (indoors versus outdoors) and access to filtering devices and other resources, but it is important that they do what they can to protect themselves – every action counts.”

—–

To donate to DRI’s scientific research on wildfire and other science that matters now, visit our DRI Foundation page or email dri.foundation@dri.edu.